Interviewed and edited by Tian

November 2024

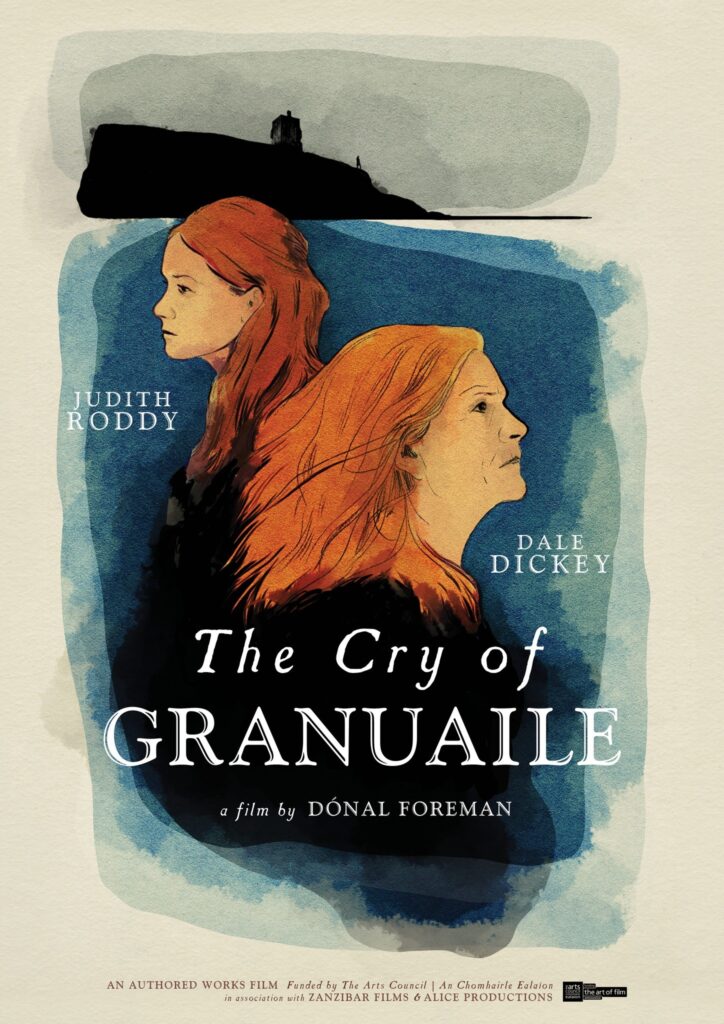

The Cry of Granuaile is a genre-defying blend of psychodrama and fantasy that follows a grieving American filmmaker and her Irish assistant as they research the story of Granuaile, Ireland’s legendary 16th-century “pirate queen.” Filmed on lush 16mm in the breathtaking landscapes of the West of Ireland, the film blurs the lines between past and present, myth and history, dream and reality. Featuring acclaimed actor Dale Dickey (Winter’s Bone, Breaking Bad) and rising Irish star Judith Roddy (Derry Girls, Say Nothing), it’s a haunting and evocative exploration of grief, intimacy, and storytelling.

Directed by award-winning Irish filmmaker Dónal Foreman, The Cry of Granuaile reflects his distinct vision and deep connection to Irish history and myth. A member of the Brooklyn Filmmakers Collective, Dónal has built a unique career bridging Dublin and New York City, crafting deeply personal and visually striking films.

In advance of the film’s streaming premiere on the Criterion Channel this December and its one-night-only screening at NYC’s Roxy Cinema, we spoke with Dónal about the creative process behind the film, its themes, and the challenges of bringing such an ambitious project to life.

Tian: You started making films at the age of 11. So how did you get into filmmaking at such a young age?

Dónal: I was already a very arty child – drawing and painting, making comic books, things like that. Then a friend’s dad had a video camera and we just started playing around with that on the weekends, doing little skits with each other and we got kind of obsessed with it. At first, everybody was swapping roles, then I started to take on the role of cameraperson. We would spend all weekend filming together and the projects got more elaborate and sophisticated. In Ireland, there’s a festival for young filmmakers called the Fresh Film Festival that we would put our films into every year. That gave us the opportunity to see our films in a movie theater with an audience, and we started winning some prizes there. It became a very formative part of my adolescence.

Could you introduce us to your film, The Cry of Granuaile? What was the initial inspiration behind the story?

The film deals with Granuaile, also known as Grace O’Malley, a 16th century “pirate queen” who’s a legendary historical figure in Ireland. She’s someone I heard stories of growing up and was always fascinated by. There’s been a few TV documentaries about her, but as far as I know there had never been a fiction film dealing with her. I’ve been thinking for years that she would be an interesting subject, but to do a historically accurate period drama about Granuaile would cost tens of millions – it would be like trying to make Pirates of the Caribbean. But it was at the back of my mind.

And then I had an unexpected source of inspiration after I moved to New York. I met with an indie film producer here who was interested in working in Ireland. He said that if I could write something for an American actress in Ireland, he could raise some funds. At first I thought, that sounds like a terrible idea, because there’s a whole history of films made in Ireland with American actors that tend to be quite cheesy and sentimental. You have these romantic comedies where the American woman comes to Ireland and falls in love, and there’s a lot of clichés around that. But I started thinking — could I do something more interesting with the idea of the American in Ireland, that could subvert some of those tropes?

So that impulse began to connect to my interest in Granuaile, and I developed this idea of an American filmmaker who comes to Ireland to research a film about her, and tours around the West of Ireland with the help of a young Irish academic. And then these themes of grief and loss and how we relate to history and memory — that all started to emerge as I got deeper into it.

Let’s dive into your creative process: How did you write the screenplay?

Well, I ended up fully financing the film in Ireland through the Irish Arts Council, which generally funds more experimental and art house films, and one of the special things about the Arts Council is you don’t need a full script to get funding from them.

I had about a five page outline of the film that didn’t even describe every scene or all of the actions or events. It was more focused on the emotional journeys of the characters and the atmosphere and style of the film. Then I wrote a detailed treatment that described most of what happened in the film, but without all the dialogue, just a few lines here and there. That treatment was maybe 30 pages long.

To turn my treatment into a full shooting script, I did something that I had also done for my first feature film, Out of Here, which was a fiction drama as well. I wrote the dialogue and fleshed out the script over two weeks of rehearsals with the actors. We went through the treatment, talked about it, sometimes doing improvisations around scenes. And then I would go home and write dialogue. The next day we would try out the dialogue that I had written and the actors would respond to it and give feedback. It was a very energizing process, and the final script came out of that.

How did you cast your actors?

We didn’t have a casting director, so it was really just me and the producers working on it. In Ireland, the film and theater world is very small and almost everybody knows everybody. There were a couple of actors, Fionn Walton and Cillian Roche, who I’d worked with before that I asked to be in it. And then everyone else I had seen in films and plays and I approached through their agent.

Dale Dickey is a character actor that I’ve seen in a lot of movies and TV shows over the years, and she’s someone whose work I really admired. She was the first person that we approached to play Maire. I just wrote a letter to her that was sent to her agent, and we were really lucky that she read it and said yes right away.

In some other cases I asked to meet with an actor and we had an “audition” that was really just a conversation. I just wanted to get a sense of who they were as a person and what they would be like to work with. Another thing I found useful was listening to actors on podcasts, so I could hear them having a long form conversation, and get a sense of their vibe and way of thinking in a way you don’t necessarily get from seeing them act in something.

What was your experience like working with Dale?

With Dale, it was really fun because I think she got to do something different than a lot of characters she’s played. She’s often cast as quite dark or scary characters – and so for her to play someone who’s an artist and has this almost childlike enthusiasm, I think she was able to bring out a different side of herself.

What inspired you to shoot The Cry of Granuaile on 16mm film?

In the story, Maire, the American filmmaker, starts shooting her own film about Granuaile, and we see glimpses of what she’s shooting as a film-within-the-film. I knew I wanted her film to be shot on 16mm because I saw her as this experimental filmmaker coming out of a New York 1980s downtown art world — some of my references for her character were people like Bette Gordon, Susan Seidelman, Vivienne Dick and Chantal Akerman.

My original plan was to shoot her film on 16mm and the rest of the film on digital – but then it became clear it was actually going to be pretty complex to rent and work simultaneously with two cameras, formats and workflows. I also realized the distinction between film and digital would mean that you would always know if you were in Maire’s film or my film, and I was interested in bringing the film to a point where those distinctions fall apart, where you’re not sure what is real or imagined or performed. So I walked myself into the situation where it just made more sense to shoot it all on film!

Where did you handle the processing and scanning of the film? Did you do it in New York or Ireland?

In London, because there’s no labs left in Ireland to do it. There’s hardly even any cameras! We actually couldn’t find a 16mm camera package to rent on the island of Ireland, and ended up getting our whole camera package from Paris because my cinematographer, this wonderful Romanian filmmaker Diana Vidrascu, she was based in France. So she could get us a deal there. We had to send the film to London and we were shooting all the way over in the West of Ireland, the opposite end of the country, hours away from the nearest big town. So we were only able to get our footage back every four days or so, we weren’t able to have dailies.

When it came to developing the visual style of the film, what specific look or aesthetic were you aiming for? What were some of your references?

Even before I had the script, I had a pretty developed lookbook of visual references from other films. Some key references for me were ’70s psychological thrillers like Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now and Robert Altman’s Images. Also several films by the Chilean filmmaker Raul Ruiz, he’s a huge inspiration to me. It was also fun to play around with the film-within-the-film because I could give Maire’s her own set of references. I thought a lot about silent film for her approach – people like Jean Vigo, who did really beautiful work in the ’20s and ’30s. As it evolved, I ended up thinking of Maire’s film as evolving through film history. It starts off like a 1920s silent film (we tried to replicate some of the film tinting effects of that era), then gradually sound is introduced and it starts to get closer to a ‘50s period drama by Bergman or Kurosawa. And then the two films start to blur together, and fuse into the same color 16mm aesthetic.

Do you use any specific structural frameworks to help engineer the storytelling, like the hero’s journey, to guide you during editing?

I didn’t think about the hero’s journey specifically, but there is a five-act framework that I like a lot and often use in breaking down my stories. From early on, I saw this film as having five distinct chapters, each of which with a different energy and a different stylistic inflection. Even when I was editing, on my timeline, I had colored markers breaking the edit down into each act. But I think of those structural things more in terms of the shape and energy of the thing, and less a dogmatic attitude of “This must happen to the protagonist on page 27” or anything like that.

For those who might not be familiar, could you share how you became involved with the Brooklyn Filmmakers Collective and how that experience has influenced you creatively?

I joined BFC about 13 years ago, right after I’d first moved to New York in 2011. I moved here without much of a plan – I had just recently acquired US citizenship because my father was American, but I moved without really knowing anybody. I didn’t have a job set up and I didn’t have any kind of community. My very first month in New York, I applied to BFC, because a Scottish filmmaker I knew, Simon Arthur, had been a member and recommended that I apply. And it’s been a big part of my life in New York ever since then, and a great way to make friends and build community, to offer support and be supported. I’ve learned a lot from the collective about how to give and receive feedback, how to listen, how to make yourself to someone else’s vision. And that’s all helped me become a better filmmaker, I think. It’s also really helped me become a better teacher – I teach editing, writing and directing at the New School and Brooklyn College at the moment and I bring a lot of skills from BFC to the classroom.

In the movie, your main character, this American documentary filmmaker is confronted with the question, “What makes you qualified to make an Irish film?” How do you feel about filmmakers creating stories outside their own cultural or ethnic backgrounds?

Well, it’s a really interesting, complicated issue. I don’t think there’s a strict rule to it.

In Ireland, there’s a lot of natural skepticism toward outsiders, especially Americans, telling our stories, and I feel some of that myself. But at the same time, some of my favorite Irish films were made by English or American filmmakers. There’s always exceptions you can point to where someone came in and actually made something really special. So with the character Maire in The Cry of Granuaile, I was interested in playing with those biases and tensions, by having a character who is indeed an annoying American in some ways – but she is also bringing an energy and creative perspective that is valuable.

But I think it really depends. If you’re an outsider making a film about another culture, you’re going to be held to a very high standard. And if you get it wrong, you’re going to get in trouble. And I think that’s fair. You have extra responsibility to be very careful, sensitive and smart about how you approach it. I think the bigger issue is less about whether someone has the right to tell a story, and more about who gets given the access, resources and platform to tell a story. When it’s easier for an outsider to get support to tell a story than it is for the people from that culture, then that’s a structural issue that should be addressed, and should be criticized.

If you could go back in time, is there anything you’d do differently during the making of this film?

Oh, a million things! I’m my own harshest critic a lot of the time. But at the same, I feel like I would never go back. I was reading recently about all the changes that George Lucas has made to his Star Wars movies over the years – he did his “Special Edition” revisions in the ‘90s, but I didn’t realize he’s actually continued to tweak them every few years. And nearly every choice he makes, makes it worse! But it’s very relatable as a filmmaker because you always see these things: “Oh, if only I’d changed that cut, or that shot…” But my instinct is no, you have to let go, move on. It is what it is. It’s a record of who you were at that time. Otherwise you’ll just drive yourself crazy. But I feel proud of what I was able to achieve on this film, despite all the flaws – and I could also do an audio commentary of the film that consisted entirely of me saying, “I did that wrong. I shouldn’t have done that. Why did I do that?”

A grieving American filmmaker and her Irish assistant tour the west of Ireland, researching a film about Granuaile, the legendary 16th century rebel and “pirate queen”. The two women develop an uneasy intimacy as they journey towards a remote Atlantic island, where boundaries begin to blur between past and present, myth and history, dream and reality…

Filmed on lush 16mm film, and starring acclaimed character actor Dale Dickey alongside a stellar Irish cast, The Cry of Granuaile is a genre-defying blend of psychodrama and fantasy from the director of the award-winning The Image You Missed.

Subscribe to get updates with more interviews.

Copyright © 2024 Brooklyn Filmmakers Collective. All rights reserved.